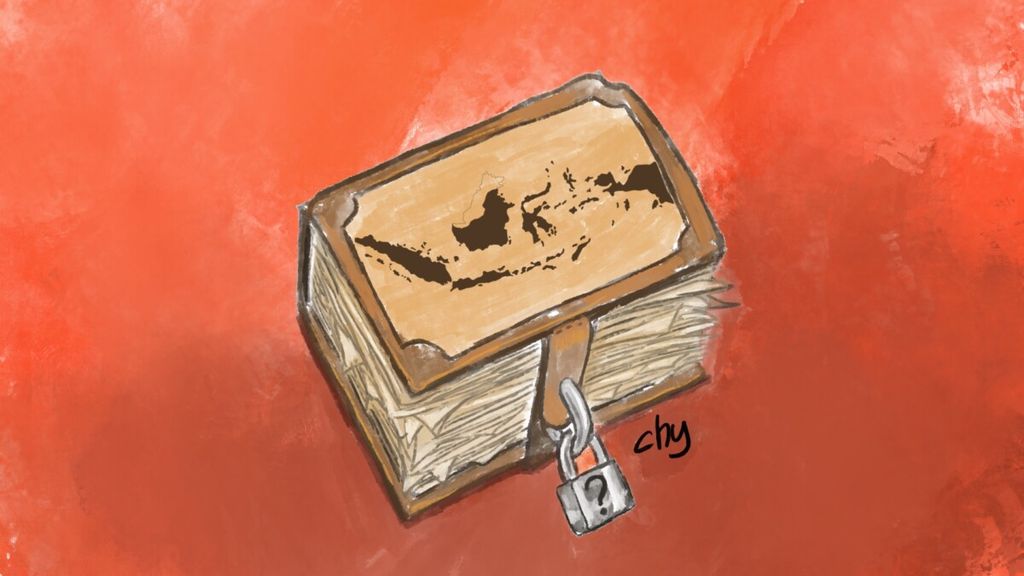

The Republic of Indonesia’s Sovereignty

The 1945 Proclamation constitutes the most important landmark in Indonesian history. But it should be admitted that a miraculous element was behind the event. The opportunity was just like hitting the jackpot.

Two miracles opened the history of the Republic of Indonesia (RI): first, the Independence Proclamation on 17 Aug. 1945; second, official world recognition of the sovereignty of the Republic of Indonesia on 27 Dec. 1949.

Nine months later, the Indonesian national flag was flown at the headquarters of the United Nations (UN) when RI was admitted as a member.

After more than 70 years, however, only the 1945 Proclamation is celebrated on a large scale in the country. The world’s recognition of the sovereignty of RI is almost entirely ignored. Why is there such a marked difference? What does it mean to us today? What will be its impact on future generations?

World recognition

The 1945 Proclamation constitutes the most important landmark in Indonesian history. But it should be admitted that a miraculous element was behind the event. The opportunity was just like hitting the jackpot. All of a sudden, Japan surrendered to the Allies at the end of World War II. The Allies were not immediately prepared to take over control from Japan. There was a vacuum pf power. The 1945 Proclamation was a super brilliant action to utilize the golden opportunity to fill the power vacuum.

During the abrupt situation, the 1945 Proclamation was hastily written and was composed of just two sentences. The first sentence announced the independence of the Republic of Indonesia. The second acknowledged the handling all fundamental affairs related to independence, a condition that was as yet unprepared. It contained no details of when and how the matter would be finalized. Nobody had any idea. The first days after it was read out, not many people were aware of the proclamation.

Also read:

> Proclamation of Independence

> Pancasila Since the New Order

On the other hand, the event in 1949 was the peak of the marathon rounds of Indonesian diplomacy over three years, which culminated in the UN-sponsored Dutch-Indonesian Round Table Conference (KMB). The process was observed by the world. The country’s people awaited its result. The agreement achieved at the conference was over 100 pages long.

Admittedly, not all circles in the country were satisfied with the Round Table Conference Agreement. President Soekarno even unilaterally annulled most of its contents in 1956. Yet, one day after the agreement was announced, President Soekarno was able to return to Jakarta from Yogyakarta with relief. Arriving in the capital city, the masses welcomed him with joy.

The 1949 event gave several lessons. First is to understand the important differences between a nation and a state. The independence of a nation does not automatically mean the sovereignty of a state. If there were any proclamation of independence of Aceh, East Timor or Papua, they do not automatically become a new sovereign state. The same applies to Sudan, Palestine or Taiwan.

President Soekarno (right) talks with Vice President Moh. Hatta regarding the formation of the Cabinet. (June 1953).

Proclaiming independence at a microphone is far easier than maintaining what is proclaimed. After the 1945 Proclamation, Indonesia was repeatedly battered by foreign troops. A number of friendly countries recognized RI sovereignty in March 1946, but it was not enough to protect the new republic.

For the UN, the various regions colonized by Europe were considered the responsibility of their former colonizers (the Netherlands, Britain, France). Before the KMB, the Netherlands insisted that the so-called armed conflict in Indonesia (1945-1949) was an “internal affair” not to be intervened by other parties. The Dutch military aggression could be halted only if the UN recognized RI sovereignty of and the Dutch invasion was declared illegitimate. So, transferring sovereignty from the Netherlands to RI was absolutely needed. Indonesia so urgently needed this official recognition that it was ready to incur a huge debt to the Dutch East Indies as compensation.

Consequently, the second lesson from the KMB is the importance of diplomatic struggle, rather than military struggle. For the newborn republic, political diplomacy at the international level was tough. The Netherlands was already a UN member and had voting rights, while Indonesia was not. Let alone a UN member, the RI did not even have observer status. Only another miracle could save the RI.

Also read:

> Unequal

The third lesson is the importance of global support for the Republic of Indonesia, especially that of the UN Security Council (SC). Indonesian sovereignty was gained not solely on the merits of RI representatives at the KMB. There were several other factors. Ironically, the main factor that triggered and prompted Indonesia’s success was a blunder made by the Netherlands.

The RI was flooded with the world’s sympathy over the Dutch military aggression of 1947-1948. As a member of the UN Security Council (UNSC) and as the RI’s first and radical supporter, Australia urged the UNSC to immediately settle the Indonesian-Dutch conflict.

The Australian proposal was backed by several other countries, including India, China and the superpower, the United States. Gradually, Indonesian diplomats were stepping towards the world forum and granted voting rights in the discussion of its case at the UN.

The event is historic. Previously, no non-UN member had been invited to speak at their own forum. The KMB was important not only for the RI, but also world history. It was the first case in which a former colony won its sovereignty through the UN process. Indonesia’s accomplishment became an inspiration for several other former colonies.

Along Jl. Malioboro, Yogyakarta, President Soekarno and Vice President Drs. Moh. Hatta was warmly welcomed by the people on (22/9/1949)

Why ignored?

The 1949 event was such a significant process and huge success for the RI in securing official recognition of its sovereignty. So why hasn’t it been celebrated with great joy in the country? It’s as though nobody cares. A number of factors are worth considering. First, until 2005, the Netherlands did not recognize Indonesian independence before 1949. In response, Indonesian nationalists rejected the nation’s history that involved cooperation with the Netherlands, including the KMB. Everything good should not refer to anything Dutch. Everything Dutch was nothing good.

In 1956, President Soekarno unilaterally annulled the greater part of the KMB agreement, including the RI’s debts to the Netherlands, the status of Papua, and Dutch companies in Indonesia. Although the New Order government revived the RI’s commitment to the remaining debts to the Netherlands (1966), elite officials silently managed the affair until its settlement in 2003.

We have demanded that the world recognize Indonesia’s independence since 1945. But until now, cries of “Merdeka!” (freedom) frequently accompany speeches.

Other factors seem to have erased the public’s memory of the historic 1949 event, such as gender. From the beginning, the RI’s independence celebrations have been focused on the armed struggle during the revolutionary period (1946-1949). For decades, 17 Aug. commemorations have been dominated by romanticism over male fighters armed with bamboo spears.

It was not only the Dutch that relied on military aggression to set up a colony that spanned from Sabang to Merauke. Indonesia was also fond of glorifying aggression, not only when it was fighting the Dutch. This historical legacy has remained up to the present in the name of religion, or the nationalism of the “unitary state”.

Indonesia’s diplomatic struggle to achieve world recognition of its sovereignty was neglected. The merits of Indonesia’s diplomats and various friendly countries have been wiped from public memory. So far, awards are very rarely granted for civilized political diplomacy at both local and global levels. The difference between a nation and state has been obscured.

/https%3A%2F%2Fkompas.id%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2021%2F11%2FAriel-Heryanto_1621490087_20211113_1636785560.jpg)

Ariel-Heryanto

We are grateful that there has lately been new enthusiasm in Indonesia as well as the Netherlands to uncover the history of decolonization. Nonetheless, this is still at an early stage and in a limited environment. The understanding of the two countries’ younger generations about their national histories is flawed for being incomplete. We have demanded that the world recognize Indonesia’s independence since 1945. But until now, cries of “Merdeka!” (freedom) frequently accompany speeches. It’s as if we ourselves are still unsure that the republic has gained its freedom.

The anti-colonial grudge against the Dutch continues to burn in our minds. The spirit of the colonizer continues to haunt us. The dawn of post-colonialism has not yet arrived.

Ariel Heryanto, Emeritus Professor, Monash University, Australia

This article was translated by Aris Prawira.