Job Without Protection

In principle, all workers -- regardless of their employment status -- must be protected in a clear written rule. There should be no discrimination in employment protection, regardless of employment status.

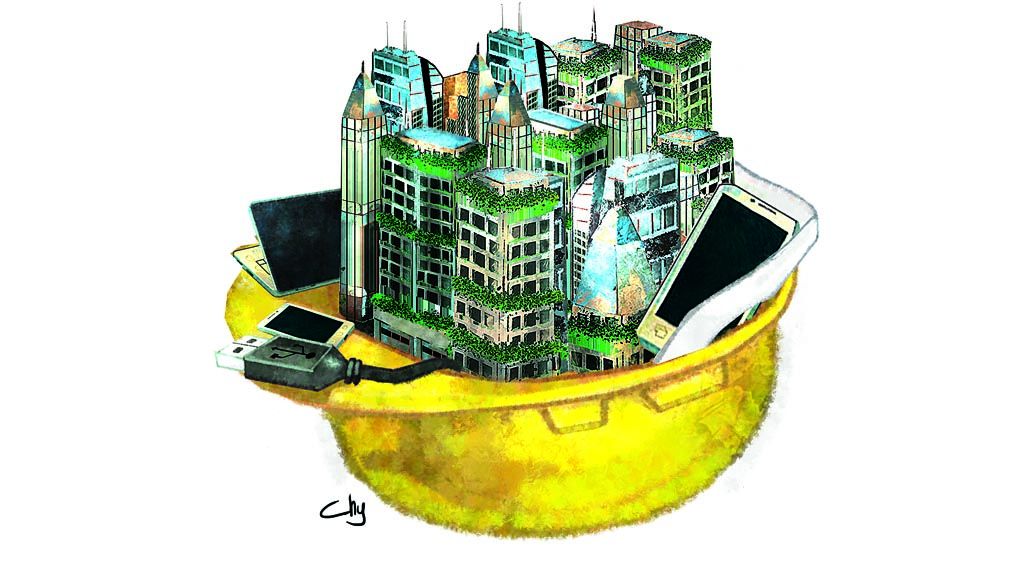

The number of vulnerable workers (precarious work) continues to increase along with the expansion of digital online business.

In fact, according to the McKinsey Global Institute, in 2021 the Covid-19 pandemic has made e-commerce business grow 2-5 times faster than before the pandemic in all countries.

Yes, if people only look at the statistics, people can misunderstand because the quantitative data seems to be improving with the growth in employment absorption. Actually, the fact is that most workers are only absorbed as vulnerable workers, working in short-term jobs and get low pay.

This proportion of vulnerable workers will continue to swell as the need for workers in the shared economy or in digital apps (PAD) expands. The above phenomenon is referred to as an inevitable consequence of globalization and the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Also read:

^ Rethinking Labor Relations and Wage Policy

^ Job Creation Law and Available Options

Governments of developing countries such as Indonesia enthusiastically welcome the presence of PAD by providing various facilities for digital investment infrastructure because it has proven to be able to solve some of the problems of scarcity of job opportunities, especially for low-skilled workers, half-employed and informal workers. This is because it has become a common characteristic in developing countries due to over-supply of work, a mismatch in the education system, millions of workers cannot be absorbed into the labor market.

So, the presence of digital workers (platform workers) has offered opportunities for workers who have so far not had a job, even if someone can have more than one job. As it turns out, there is no chance without risk. The new job opportunities created by digital technology present a major problem for job protection. Especially in terms of wage protection, working hours arrangement, social security protection and freedom of association and bargaining.

The presence of digital workers has triggered the emergence of a deconstruction of conventional industrial employment relations due to the absence of legal rules for PAD due to unclear relations between employers and employees. The only rules available so far are Transportation Ministerial Regulation (Permenhub) No. 12/2019 concerning the safety of motorcycle users, and a land transportation director general regulation regarding the top and bottom tariff limits.

Regulatory vacuum

As a result of the absence of clear rules, the work relationship between the app owner and the PAD only occurs in the form of a one-sided arrangement by the app owner. This is because, as stated in Article 15 of the Permenhub above, the relationship between the app company and the drivers is a partnership relationship, not an industrial work relation as regulated in the Manpower Law.

From the experience of other countries, several countries have regulated digital workers. Indonesia is among the countries that are not ready to change the laws and regulations. This reluctance is seemingly due to the sufficient contribution of the digital app business to provide job opportunities. If it is strictly regulated, it is feared that it will hamper its growth.

The biggest growth of digital worker business currently occurs in digital transportation workers (PTD). According to estimates by the chairman of the National Presidium for the Indonesian Two-Wheeled Action Association (Garsa), Igun Wicaksono, there are currently 3.9 million PTD in Indonesia. Consisting of 2.9 million Gojek drivers and 1 million Grab drivers. Indeed, this data is only an estimate due to the absence of data that is properly available from the digital manager and the government. But of all these workers, according to BPJS Ketenagakerjaan data in 2020, only 95,766 (3.3 percent) have registered as participants in the Workers Social Security (Jamsostek) program, consisting of 93,118 drivers at Gojek and 2,648 drivers at Grab.

Also read: Job Opportunities in the Changing World

This is just one example of low social security coverage.

There are still cases of wages, working hours and so on. Who is to blame for this problem? Because the owners of digital apps do not think they are committing a legal deviation from their business practices. By legal definition they are not employers or worker employers.

They are simply providers of applications to drivers with a revenue-sharing agreement. No work relationship! This is because Article 1 number 15 of Law No. 13/2003 concerning Manpower stipulates, "An employment relationship is a relationship between an entrepreneur and an employee or laborer based on a work agreement which has elements of employment, wages and instructions."

One element that is not fulfilled in this definition is that PAD does not get wages from the application owners, but from consumers who use their services. Digital managers are only providers of technology facilities that help drivers get passengers and provide digital payments with revenue sharing agreements.

Prevent dehumanization

It is undeniable that technology has replaced many workers, preventing them from heavy, hazardous and repetitive work. Hence, the efforts to prevent some degree of dehumanization could be avoided. The presence of artificial intelligence technology, algorithmic technology, and reader machine allows application owners to monitor workers’ activity beyond the accuracy of conventional HR manager supervision.

Technology can monitor the movement of workers every second, know where they are and provide early warning of unattainable targets. It is based on these data scores that the fate of digital workers is generally decided. For example, who are the drivers that work inefficiently, work on time or exceed the target. Layoffs no longer happen through a consultation mechanism as regulated by the Manpower Law, but are based on input obtained from technology.

Likewise in terms of wages, it no longer refers to the minimum wage regulations. There is a daily target as a basis for determining income. If the worker can exceed the target, an additional bonus is awarded. Some of the digital transport workers whom the authors interviewed complained about their recent lack of income.

In his early days working as a driver of digital apps, the income was very high, but the emergence of several other competitors has resulted in reduced income. Drivers who experience work accidents must pay for the treatment themselves because they are not Jamsostek participants. In this situation they are the workers who fall most quickly into the abyss of absolute poverty.

BPJS Ketenagakerjaan data confirm the above facts, with data on the high rate of work accidents every year. In 2020, there were 350,000 work accidents. This means an average of 300 accidents per day. This data is of course still higher than the reality of the actual level of work accidents, because this figure only takes into account the 19 million active participants of Jamsostek.

Also read: “Omnibus Law”, Between Labor and Productivity

Outside of Jamsostek participants, there are still tens of millions of drivers who have not registered with Jamsostek. For PAD, only 95,766 have Jamsostek protection. Apart from the above problems, another dimension of dehumanization also affects PAD workers in the process of recruitment, promotion, layoffs, wages and other things, because then the determination of these matters is no longer determined by the HR manager, but by the algorithm automatically inputted into the application system.

A survey by the International Labor Organization (ILO) in 2019 shows that the proportion of workers who are covered by social security is still small. In Africa it is 45 percent, Latin America 38 percent, Asia 38 percent. Still in the ILO survey, 65 percent of workers work at least six days per week, and 44 percent work seven days per week. As many as 56 percent work from night to morning, and 68 percent work at night from 6. p.m. to 10 p.m. The high volume of work faced by digital workers makes the concept of flexible work and work-life balance an illusion.

Global and national solutions

Recently, there has been an international debate over a new idea known as universal basic income. The core idea is that the government will provide basic income to everyone who is unemployed at working age, to mitigate job losses due to the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Some economists call it "a post-capitalist economic system", a direction toward a state-based concept of welfare. The funds are taken from two sources: the imposition of tax from gas emissions (emissions tax) and from the transfer of social security contributions that have been collected so far (ending social security pay roll). The problem is that this concept is still very complicated to implement. It seems only suitable for a rich country with a small population. A poor country with a large population will be faced with a lack of fiscal capacity to finance.

Other economists who oppose this idea say that the policy on protection of work is more important to regulate than income protection. The reason is that the work protection concept provides a mechanism for negotiating wages and other working conditions, as one of the important properties of industrial relations. Meanwhile, if the priority is only income protection, workers who get compensation can reduce their motivation to look for work, such as tried in Finland.

Also read: A Labor Day Full of Anxiety

Indonesia, which is facing the rapid growth of its PAD sector, urgently calls for such regulation. The first priority that must be determined is the certainty of the legal status of PAD because currently there are several categories that have been defined according to their respective legal interpretations. There are those who classify them as workers who receive wages; not a wage earner (employee without an employer); non-contract workers, micro and small entrepreneurs.

Several countries have succeeded in establishing the status of PAD in official regulations. This experience can serve as a reference for Indonesia in determining the legal status of PAD. France, for example, through a long debate in the Constitutional Court for four years, has finally succeeded in producing the Mobility Law which contains regulations for PAD, although it only applies to car and motorcycle drivers.

In this law, the status of PAD workers is stipulated as contract workers. So, all the laws protecting contract workers apply to PAD. These include the right to establish labor unions, collective bargaining, minimum wages, social security rights and the right to strike. The same arrangement also applies in South Africa, where Uber drivers have the right to associate, negotiate and strike, because their status is workers, not independent contractors.

The governments of India, Britain and China have also made rules on the clear legal status of PAD. Even in China, there are rules that app owners must ensure that drivers are protected by social security. The general argument for establishing this legal status is based on the fact that digital application business owners have the power to issue work orders, monitor workers\' performance and can even impose sanctions if the workers make a mistake.

Thus, a subordinate relationship of employment is clear, which justifies an employment contract agreement. PAD cannot be seen as independent or independent workers because in reality they are not free to choose who the passengers are, the amount of pay, work area, working hours and so on. That is why the Belgian government imposes a tax on digital worker businesses, the proceeds of which are allocated to fund PAD social security contributions.

India also makes almost the same tax regulations, but the tax collection mechanism is carried out by application business owners by adding service taxes to each passenger to finance the PAD social security contributions. In Indonesia, app business owners sporadically and minimally protect only a small portion of PAD for the BPJS Ketenagakerjaan program, but not in a clear regulation, so not many PAD can be protected.

Rekson Silaban

In principle, all workers -- regardless of their employment status -- must be protected in a clear written rule. There should be no discrimination in employment protection, regardless of employment status. However, at the time of this writing, there are thousands of PAD who are currently lying sick due to work accidents, thrown into poverty, without government, without labor unions.

Rekson Silaban, Analyst at Indonesia Labor Institute

This article was translated by Kurniawan H. Siswoko.