Helping the "Healthy"?

This article is intended to provide several reflective notes on the fiscal and monetary policy responses launched by the financial authorities in dealing with the impact of Covid-19.

/https%3A%2F%2Fkompas.id%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F04%2F20200402_ENGLISH-HL_C_web_1585836783.jpg)

Finance Minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati (center left, foreground) hands over a Presidential Letter to House of Representatives (DPR) Speaker Puan Maharani (center right, foreground) at the Senayan legislative complex in Jakarta, Thursday (2/4/2020). The Presidential Letter proposed a series of legal adjustments for reallocating funding from the state budget to a Covid-19 emergency fund.

This article is intended to provide several reflective notes on the fiscal and monetary policy responses launched by the financial authorities (both the government and Bank Indonesia) in dealing with the impact of Covid-19.

The main thought that the writer wishes to convey is that there is an urgent need for us to rethink the political mandate given to fiscal or monetary authorities in the future, especially in coordinating in the financial sector to address development and welfare-related issues in the future.

New fiscal political consensus

The first reflection, there is an impression of a "new political consensus", though not strong enough, not to be caged in a fiscal deficit of under 3 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). This is evident in the provisions of Regulation in lieu of Law (Perppu) No. 1/2020, which is contained in Article 2, Paragraph 1a. This article, among others, states that during the mitigation of Covid-19, the budget deficit could exceed 3 percent of GDP and will return to the highest threshold of 3 percent in 2023.

As we know, the 3 percent threshold is a technocratic norm to discipline fiscal authority introduced to European countries through the Maastricht Treaty in 1992. It is not just a threshold of a 3 percent budget deficit. The recommended public debt threshold should also not exceed the 60 percent limit of GDP. In this regard, the technocratic norm about the loan threshold of 60 percent of GDP is still held in the Perppu. The change is only the threshold of the budget deficit ratio, which can now exceed 3 percent of GDP.

Also read : Minimal-Contact Economy

Actually, the 3 percent deficit threshold recommended by the Maastricht Accord is also similar to one of the 10 policy prescription points contained in the Washington Consensus in 1989. The Washington Consensus also suggests the need to maintain fiscal discipline, where the deficit should be maintained below 2 percent of GDP. For Indonesia, this technocratic norm is not only a policy consensus among technocrats and mainstream economists but has also been embedded into a positive legal norm in the form of highly binding legal provisions. State Finance Law No. 17/2003 Article 12, Paragraph 3 clearly and expressly states that the budget deficit is a maximum of 3 percent of GDP and the loan amount is limited to a maximum of 60 percent of GDP.

The need to embrace fiscal discipline seems to start from the following idea. The government is said to have a tendency to carry out "excessive" fiscal expansion policies that create uncontrolled inflation and a huge debt burden. The fiscal policies are indeed very vulnerable to political pressure and persuasion to increase the size of the state budget.

Also read : Post-Coronavirus Awakening

Increasing the amount of the state budget, for example, is very easy to morph into a fun instrument and win a political constituency. The state budget can also easily accommodate the populist sentiment in order to build and win electoral support in general elections. In the effort to neutralize the strength of this political variable, there is a consensus to create a threshold for the budget deficit and public debt loans. The point is to minimize fiscal risks for the government in the future.

However, it is difficult to deny the fact that the fiscal authorities have a huge responsibility to make economic changes. In addition to the authority to obtain revenue through tax and non-tax revenue, the fiscal authorities play a key role in expenditure. Politically the spending authority is validated through various major issues such as funding the development, spurring the growth, up to distribute the welfare. For the development and growth of fiscal instruments in expenditure it is allocated through capital expenditure for infrastructure development.

Meanwhile, on the issue of welfare, the fiscal instrument can launch various policies through the social security system and subsidies to the education and health sectors and to marginalized groups through social spending. In practice, when the fiscal deficit grows, one of the policy options is financing strategy by creating debts (debt issued financing).

Because of this kind of political mandate, fiscal policy does indeed have an institutional nature that is vulnerable to excessive spending (fiscal profligacy). There is a political fact that no government carries out a campaign to reduce the state budget if it wants to win electoral support in competitive elections. The fact is that each government increases its spending budget every year bigger than in the previous year. Because of the political inducement which is inherently attached in the nature of fiscal authority like this, George P. Schultz et al (2016) once stated that there must be a clear separation between the authority to print money and the authority to spend it. In this context of understanding, we can accept the logic and political consequences of why there is a push to make the central bank independent.

Helping the ”healthy ”

The second note, while fiscal adjustments have been made, the monetary authority in this case BI seems to have not moved from the old paradigm. BI has been an independent central bank since 1999, referring to Law No. 23/1999 concerning BI. In this context of independence, BI is no longer given the burden of responsibility to act as an agent of development as before. The focus of its policy is inflation control and exchange rate stability. Issues and targets for development and welfare are seen only as a long-term result of the success to control inflation and the exchange rate.

In this paradigm context since 2005, BI has applied the principle of inflation targeting framework (ITF) as the basis for carrying out its monetary policy. Although not stated in the positive legal norm such as the State Budget, the ITF principle in Europe ideally targets inflation of around 2 percent. There is a strong belief that with an inflation target of 2 percent, the output gap problem (the gap between the supply and demand sides) can be controlled.

However, it should also be noted, this ITF principle has also received some notes of criticism related to the effectiveness of low inflation on economic growth. One economist who criticizes the central bank\'s monetary policy which is too focused on inflation is Gerald Epstein. He is of the opinion that the central bank should not only focus on handling inflation, but also economic growth through employment (Central Banks as Agents of Employment Creation, June 2007).

Also read : Post-Covid-19 Indonesia

/https%3A%2F%2Fkompas.id%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F02%2F20200227_ENGLISH-OPINI_B_web_1582814004.jpg)

President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo and Vice President Ma\'ruf Amin chair a meeting with Cabinet ministers and heads of government institutions at the Presidential Office in Jakarta on Tuesday (25/2/2020). The meeting was called to discuss the impact of the recent coronavirus outbreak on the Indonesian economy.

Furthermore, Epstein states that high inflation is not always dangerous for the economy, given the potential output loss that might occur as a result of low inflation. By maintaining its independence from the executive, the central bank is also perceived to be even more dependent on financial market players.

There is anxiety from Epstein that the independent central bank seems to be trying hard to meet the interest of the financial sector, namely protecting the rate of asset inflation through the implementation of low inflation and high real interest rates (see, Gerald Epstein, Financialization, Rentier Interests and Central Bank Policy, 2001).

In this regard it is interesting to note that in the current difficult situation Bank Indonesia has conducted policy intervention through the expansion of liquidity to the financial markets known as quantitative easing (QE). Based on the latest data, the total liquidity expansion is estimated at Rp 605.5 trillion. This QE policy instrument is carried out through the purchase of Government Securities (SBN) on the secondary market at Rp 166.2 trillion, a reduction in statutory reserves of Rp 155 trillion, banking term repo of Rp 160 trillion, foreign exchange swap of Rp 36.6 trillion, and the easing of the fulfillment of macroprudential intermediation ratio of Rp 15.8 trillion, and banking term repo and foreign exchange swap of Rp 71.9 trillion.

Also read : Adapting to Recession

However, it must be noted that the character of the process of transmitting the liquidity expansion will not directly impact the real sector and lower economic groups.

This QE instrument is used more as a safety net to protect financial markets from possible turbulence. By following Epstein\'s mindset, for example, liquidity expansion might be perceived as a policy response to save a group he called the rentier interests. Another criticism is that the magnitude of the amount of liquidity expansion might have very different effects if it were distributed through a mechanism that is called by Milton Friedman as helicopter money. Therefore, politically, this liquidity expansion policy seems to increasingly help those who are "healthy" than those who are "sick". This liquidity expansion also seems to favor the actors on the supply side rather than on the demand side.

Also read : Enforcing New Normal

House Speaker Puan Maharani chaired the DPR Plenary Meeting at the Parliament Complex, Senayan, Jakarta, Tuesday (12/5/2020).

Foreign loans are increasing?

Third reflection note, related to the coordination between fiscal and monetary that needs to be strengthened. There are signals where there is a shift in the fiscal policy deficit norm that can exceed the 3 percent threshold, but BI does not appear to want to change the ITF principle that is increasingly protecting the financial sector, so that the fiscal authority will have difficulty in performing the debt issued financing.

Especially those related to issues of welfare distribution and investment commitments that want to be maintained to carry out development and growth in the years to come. The difficulty faced by the fiscal authority can be seen from the processing of figures from secondary-media sources. The identification carried out shows that the debt issued financing strategy will not be easily realized. Initially, the Finance Ministry estimated the need for the issuance of SBN at Rp 856.8 trillion over the remainder of 2020, while the total debt financing was estimated at around Rp 1,439 trillion by early May 2020.

The amount of financing of around Rp 1,439 trillion comes from the debt repayment obligations due of around Rp 433 trillion, deficit financing of Rp 853 trillion, and investment and other financing of Rp 154 trillion. As far as this article is published, the need for the Finance Ministry apparently can only be covered by BI through a QE strategy of Rp 125 trillion by buying SBN on the primary market.

Also read : Predicting Growth Momentum

However, there had been changes in the past month. Until the time this article was written, the budget deficit post itself had experienced at least four adjustments. Before the pandemic, the deficit was estimated at 1.76 percent or Rp 307.2 trillion in the 2020 State Budget. However, this figure was changed to 5.07 percent or Rp 859.2 trillion through the implementing regulation of Perppu No. 1/2020, namely Perpres (presidential regulation) No. 54/2020 . It is believed that the government might increase the deficit rate to 6.34 percent (Rp 1,039.2 trillion).

Previously the government issued a deficit figure of 6.27 percent (Rp 1,028.5 trillion). Using the assumption of a 6.34 percent state budget deficit or Rp 1,039.2 trillion, debt financing needs will increase to Rp 1,647.1 trillion, of which Rp 1,002 trillion will be funded from SBN. The realization rate of the debt financing itself until May 2020 had reached Rp 568.5 trillion, consisting of Rp 531.5 trillion from SBN and Rp 37 trillion from loans. Thus, until the end of 2020, it is estimated that the central government still needs another Rp 1,078.6 trillion. This requirement will be obtained from the issuance of SBN amounting to Rp 967.6 trillion, and loans of Rp 111 trillion.

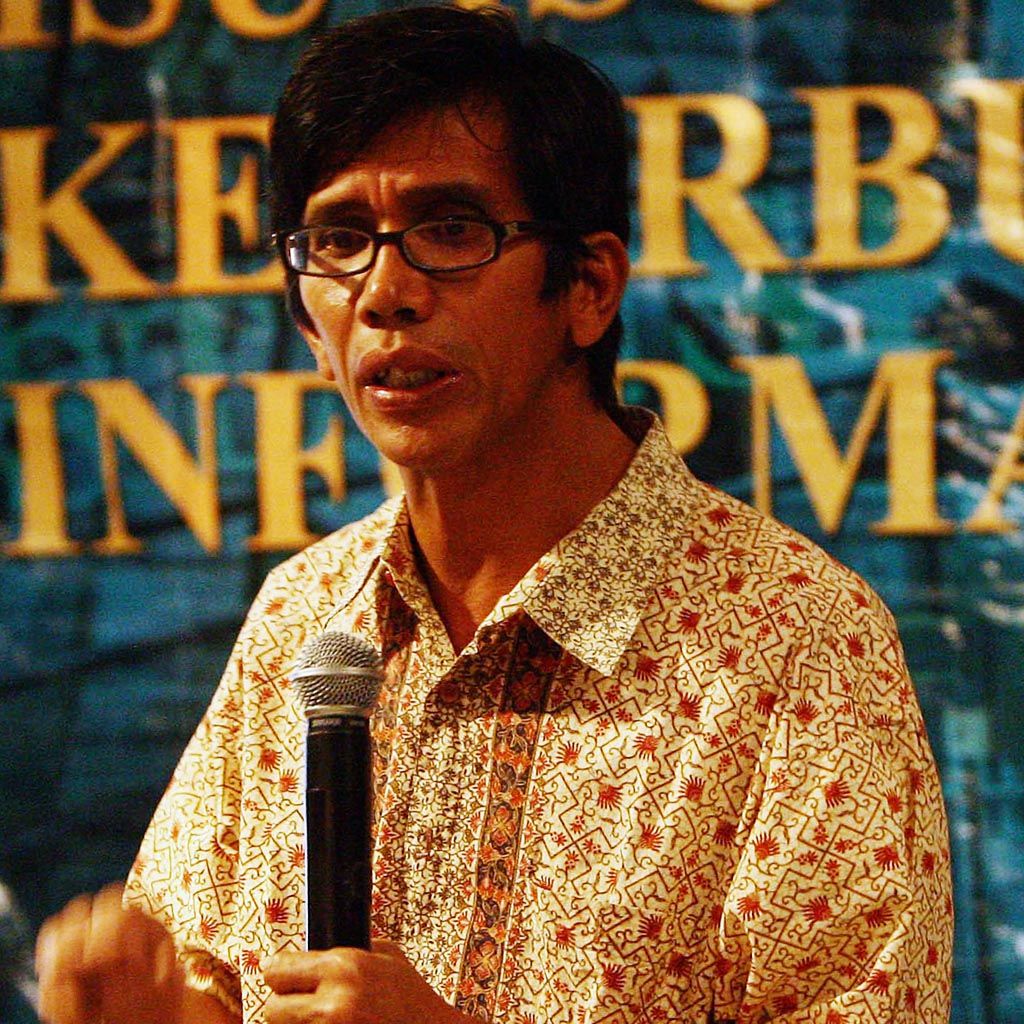

Makmur Keliat

Therefore, it is likely that the dependence of Indonesia\'s macroeconomic stability on foreign loans will increase in the coming years. There are three options available. First, SBN issued will likely be bought by investors who do not reside in Indonesia, both institutionally and individually. Another option, relying on loan financing from international institutions. The Asian Development Bank on 23 April approved funding assistance of US$1.5 billion. The third option is the policy mix between the two options. All of these options will continue to make Indonesia\'s vulnerability to the dynamics of global financial markets remain high.

Makmur Keliat, Lecturer of Political Economy, Department of International Relations, the School of Socio-Political Sciences (FISIP), University of Indonesia.