The Dangers of Data-Blindness

In this modern age, global societies have become increasingly competitive and demand measurements based on facts and data in planning, evaluating and criticizing the government’s plans for the future. Many have become data literate.

Indonesia and many other developing countries remain stuck in a culture of data illiteracy and authoritarian, verbal-focused communications. Communication that focuses on measurable data based on properly understood measurements remain marginalized.

Developed countries are blossoming with their evidence-based development policies that bring effective results. Meanwhile, Indonesia and other developing countries are lagging behind, gasping for breath. In these countries, development policies bring less effective results. Data blindness has undermined the effectiveness of policy. The gap in mastering data between developed and developing countries is ever increasing.

Data blindness and meaning

Data blindness is defined as a sense of alienation and incomprehension in delving into the meaning of statistical data. In Indonesia, this tendency can be found practically everywhere: among the general public, intellectuals and in executive and legislative state bodies. It has undermined efforts to develop the nation and foster productive public debate.

The central and regional governments often use data as mere accessory. Development plans always include data, but there is often a lack of coherence between the figures presented and the policies proposed. Sometimes, the policies don’t even make sense according the figures.

The following is a list of examples. Many regents in remote regencies are often proud of their region’s low unemployment rate. They make speeches about this and proudly claim to have pushed down the unemployment rate. They say things like, “Central Statistics Agency [BPS] data shows that our region’s unemployment rate is only 2 percent, whereas the national average is more than 5 percent!”

If they actually understood the data’s meaning, surely they would have observed the pattern of interregional distribution of unemployed people. Consequently, they would have understood that, of course, the unemployment rate would be higher in regions where development is concentrated. Herein lies the migration law, where job seekers will always leave disadvantaged regions for centers of development where more jobs opportunities are available. Where there is sugar, there are bound to be ants.

Sometimes, our economics experts are also trapped in such a mindset. Perhaps this is because the majority of economics literature at their universities abroad taught them that a low unemployment rate means a good economy, and vice versa. We often forget that, because of population mobility, there is a stark difference in how unemployment rates in urban centers and in rural areas are interpreted.

Another example is that we often lack proper understanding on how to improve our Human Development Index (HDI). How can we truly catch up with our neighbors and ensure that interregional gaps are closing if we misunderstand the HDI data? The opposition and the public criticizing the government’s policies also often misunderstand the data.

For instance, improving the HDI’s health component in many regions often involves reducing the general fatality rate, such as through reducing traffic accident deaths from and improving education for diseases connected to an unhealthy lifestyle. While this is correct, it needs to be done in the context of improving public health as a whole. Such policies are surely related to the HDI, but they have minimal effect in relation to HDI components such as life expectancy at birth.

The HDI’s life expectancy component does not cover general life expectancy and is limited to life expectancy at birth, which is measured by the infant mortality rate. It is true that the infant mortality rate reflects the degree of success of development plans. However, if we truly wish to accelerate increasing the HDI, why not focus our attention to the core determinants of the infant mortality rate? As a result, even with varied programs and huge funding to boost the HDI, we often do not achieve the intended results.

Many observers simply divide the poverty line’s minimum per capita monthly income of Rp 402,000 (US$27.88) by 30 (days) to result in a per capita daily income of Rp 13,000. Fierce debates on this figure then ensue. This is despite the fact that the poverty line varies between households depending on the number of family members. A family of five, for instance, will only be officially declared poor if their total income is Rp 2.02 million per month. Is this line too low? Of course, as it only covers people who can fulfill only their most basic needs.

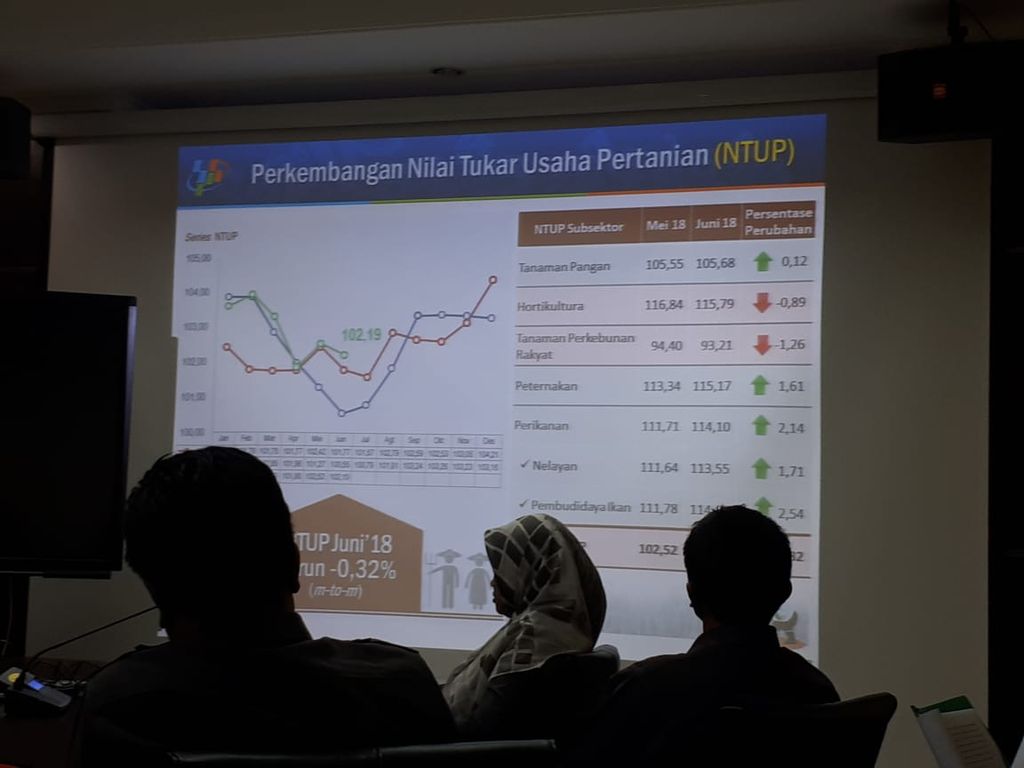

It is the same when we talk about the gross domestic product (GDP), the gross regional domestic product (GRDP), farmer exchange value, inflation and many other topics. Debate often ensues without proper understanding of the data’s actual meaning.

Endangering the nation

The cultural of numerical data has never been part of our historical tradition. Ours is more of a verbal culture: qualitative, normative and sometimes subjective. It is understandable that there is often a lack of correlation between the available data and public debate; or between data-based evidence and actual development programs.

We are increasingly lagging behind advanced countries with their tradition of data-driven debate. Criticizing the government’s policies based on properly understood data is the trait of a society that is based on science.

In Indonesia, due to the high rate of data blindness, debates over development are often merely verbal: they sound nice, but have poor foundations. Due to their verbal and sometimes authoritarian nature, insult and prejudice reign. Such tendencies are not only unfortunate; they are also dangerous to our sustainability as a nation.

It is interesting what UN expert statistician, former statistics director and chief statistician of the OECD and former Italian labor and social policies minister Enrico Giovannini said: “If a society does not know where it stands, it is quite difficult to decide where to go. Data have a key role in helping policymakers and citizens to understand facts correctly and design their future strategies. The accountability of public debates, public policies and the democratic control on politicians’ decisions can be improved if statistics [and] data is placed at the center of public debate.”

We believe that accelerating national progress is only possible if we adopt a new tradition in planning, criticizing and evaluating our nation’s policies and future target. This is the tradition of numerics and data culture. We should strive to minimize our data blindness rate. (JOUSAIRI HASBULLAH, Chief Technical Advisor (2012-2015) and Steering Group (2017-June 2018), Social Statistics Asia and the Pacific; Alumni, Flinders University Australia)